1. What do I know about this stock that other investors don't?

Every investor who has ever bought a stock believes it to be undervalued or under-appreciated by the market, but before you press the "buy" button it's absolutely critical to think about your competition and what it might know and not know. If the market agrees with your thesis, for instance, there isn't much room for outsized growth.

After all, there are myriad analysts and investors who know a given industry inside-and-out and at least a few of them probably have better access to information, management, suppliers, and customers than you do. So, what might they be missing?

If you're looking at a large-cap stock, perhaps it's that the market is thinking too short-term or is under-appreciating the company's longer-term advantages. If you're looking at a small-cap stock, maybe it's that institutional investors have yet to pick up on the opportunity. Whatever the answer might be, be sure that you have an answer to this question before buying the stock.

2. Does this company have a sustainable competitive advantage?

A company doesn't necessarily need a sustainable competitive advantage to make it a good investment, but if you're assuming robust growth, generous profit margins, and high returns on equity in your forecast then it's imperative to be able to identify the source of the company's competitive advantage.

If you can't determine a source, then the company probably doesn't have a competitive advantage and it may be necessary to revisit your assumptions.

If you can determine the source of sustainable competitive advantage, the next question to ask is "How long do I expect this advantage to remain intact?" Eventually, competitive forces will begin to chip away at the company's defenses and very few companies can keep competitors at bay for more than five years. Be fair, but be realistic with your assumptions.

3. If the stock loses 50% of its value over the next three years, what happened?

Some investors call this the "pre-mortem" test. The idea is to identify potential thesis-destroyers before they materialize and hopefully help you sidestep a permanent loss of capital.

Once we've become bullish (or bearish) on a stock, it's natural to place a higher value on information that affirms our thesis and overlook or dismiss important risk factors. By forcing ourselves to consider what could go wrong, we can break that dangerous positive-feedback loop and better understand the risks before investing.

4. In two minutes, can I explain to a friend how this company makes its money?

Some companies have very straightforward business models while others can be extremely complicated with half-a-dozen reporting segments, joint-ventures, or merger activity.

If you can't make a succinct elevator pitch to a friend, describing how the business works -- that is, how money flows from customers to the company and then how the company uses, reinvests, and distributes that cash to shareholders -- it's probably not a stock you should own.

5. When will I sell this stock?

Even if you're a dyed-in-the-wool buy-and-hold investor, there are still circumstances where it might behoove you to consider selling the position. For example, the stock could greatly exceed your fair value estimate, a better opportunity could present itself, or your original thesis could be broken.

The important thing is to have some type of exit strategy established so that if and when that situation presents itself, you'll be less likely to second-guess your decision.

Share your questions

What questions do you ask yourself before buying a stock? If you'd like to share, please add them in the comments below.

Thanks for reading! Hope you had a nice weekend.

Best,

Todd

@toddwenning on Twitter

Sunday, October 28, 2012

Sunday, October 21, 2012

An Important Misunderstanding About Dividends

My interest in dividends began during a previous job in which I helped manage the portfolios of ultra-high net worth individuals.

In many cases, the account owners had bought their stocks decades earlier, never touched them, reinvested their dividends, and were now living off the dividends from those investments without needing to touch the principal. The principal was then typically passed onto children and grand-children who were always, of course, appreciative of grandpa's or grandma's wise investment decisions.

This approach to investing was radically different from what I had previously understood investing to be -- that is, trading and taking bets on the next "big" thing. Patient dividend investing seemed a much more reasonable (and rational) approach for an individual investor and the bulk of my own investments today remain aligned with this valuable strategy.

As I learned more about dividend investing, I came across a number of academic studies and books that suggested that the vast majority of long-term returns from stocks were attributable to dividends. Indeed, these studies fit nicely with my experiences working with the wealthy investors who harnessed the power of dividends to build their family fortunes.

Looking more closely at these studies, however, I found that they assumed 100% dividend reinvestment, which overstates the contribution of dividends to long-term returns.

Earth to the ivory tower...

The 100% reinvestment assumption is simply not practical. Taxes, for one, can prevent full reinvestment as can commissions, the inability to reinvest in fractional shares, and an investor's decision to spend or save the dividend rather than reinvest it.

A 2011 paper by Legg Mason's Michael Mauboussin sheds much light on this topic and correctly emphasizes the distinction between the equity rate of return (price appreciation plus dividend yield) and the capital accumulation rate (returns including reinvested dividends).

Mauboussin provides two helpful formulas to help us understand the math behind total shareholder return (TSR).

1.) TSR = g + (1+g)*d

Where:

g = the annual price appreciation rate

d = dividend yield

This TSR formula assumes 100% reinvestment of dividends and is likely the one used in the previously referenced academic studies. To illustrate, a stock that's growing at 7% per year and has a 4% starting dividend yield should generate TSR of 11.28% annualized (0.07 + (1 + 0.07)*0.04).

TSR equals the capital accumulation rate (CAR) only when there's 100% reinvestment. The following formula shows the CAR when there isn't 100% dividend reinvestment. It's the same formula as the first, with a slight modifier that incorporates rate of reinvestment.

2.) CAR = g + (1+g)*d*r

Where:

r = % reinvested

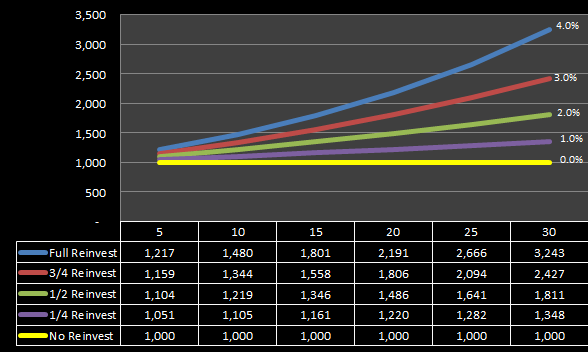

To show how various rates of reinvestment can dramatically affect long-term returns, the following chart and table assume a $1,000 investment in a stock with a starting dividend yield (d) of 4% and annual price appreciation rate (g) of 7% at various rates of reinvestment over time.

As you can see, anything less than full reinvestment results in a lower CAR, and price appreciation rather than dividends accounts for a larger and larger percentage of the results. If the investor chooses to reinvest nothing and instead chooses to consume the dividend, the only source of growth is price appreciation.

To further illustrate the importance of price appreciation in returns, let's assume an annual price appreciation rate (g) of 0% at various rates of reinvestment.

Over 30 years assuming 100% reinvestment, a $1,000 investment in a stock with an initial dividend yield of 4% and price appreciation of 7% will be worth $24,690; if price appreciation is 0% it will be worth $3,243. When there's no price growth, you're just purchasing additional shares.

In other words, while we can clearly see the importance of reinvesting dividends in enhancing the benefits of compounding growth, we can also see that price appreciation matters more than the oft-cited studies suggest.

This isn't a dividend downer

By no means should this be taken as a knock on the power of dividends. Rather, it shows that investors also need to pay attention to price appreciation and valuation. Dividends alone don't drive returns.

While the academic studies over-emphasize and perhaps misrepresent the contribution of dividends to long-term shareholder returns, the studies remain an important part of the discourse about dividends and illustrate quite clearly how dividends enhance the benefits of compounding growth. Their lessons should still be heeded.

The more fully you can reinvest each dividend received, the higher your potential longer-term returns. A few ways that you can maximize your reinvestment rate are to hold your dividend paying stocks in tax-advantaged accounts like IRAs (US) and ISAs (UK), to compare your broker's reinvestment fees (if any) and policies (do they allow fractional reinvestment?) versus others, and to evaluate your reinvestment strategy.

Thanks for reading! Please post any questions or comments below.

Best,

Todd

@toddwenning on Twitter

Note: In the original post, I mislabeled CAR in the second formula and in the examples. It has now been updated. Apologies for the confusion.

In many cases, the account owners had bought their stocks decades earlier, never touched them, reinvested their dividends, and were now living off the dividends from those investments without needing to touch the principal. The principal was then typically passed onto children and grand-children who were always, of course, appreciative of grandpa's or grandma's wise investment decisions.

This approach to investing was radically different from what I had previously understood investing to be -- that is, trading and taking bets on the next "big" thing. Patient dividend investing seemed a much more reasonable (and rational) approach for an individual investor and the bulk of my own investments today remain aligned with this valuable strategy.

As I learned more about dividend investing, I came across a number of academic studies and books that suggested that the vast majority of long-term returns from stocks were attributable to dividends. Indeed, these studies fit nicely with my experiences working with the wealthy investors who harnessed the power of dividends to build their family fortunes.

Looking more closely at these studies, however, I found that they assumed 100% dividend reinvestment, which overstates the contribution of dividends to long-term returns.

Earth to the ivory tower...

The 100% reinvestment assumption is simply not practical. Taxes, for one, can prevent full reinvestment as can commissions, the inability to reinvest in fractional shares, and an investor's decision to spend or save the dividend rather than reinvest it.

A 2011 paper by Legg Mason's Michael Mauboussin sheds much light on this topic and correctly emphasizes the distinction between the equity rate of return (price appreciation plus dividend yield) and the capital accumulation rate (returns including reinvested dividends).

Mauboussin provides two helpful formulas to help us understand the math behind total shareholder return (TSR).

1.) TSR = g + (1+g)*d

Where:

g = the annual price appreciation rate

d = dividend yield

This TSR formula assumes 100% reinvestment of dividends and is likely the one used in the previously referenced academic studies. To illustrate, a stock that's growing at 7% per year and has a 4% starting dividend yield should generate TSR of 11.28% annualized (0.07 + (1 + 0.07)*0.04).

TSR equals the capital accumulation rate (CAR) only when there's 100% reinvestment. The following formula shows the CAR when there isn't 100% dividend reinvestment. It's the same formula as the first, with a slight modifier that incorporates rate of reinvestment.

2.) CAR = g + (1+g)*d*r

Where:

r = % reinvested

To show how various rates of reinvestment can dramatically affect long-term returns, the following chart and table assume a $1,000 investment in a stock with a starting dividend yield (d) of 4% and annual price appreciation rate (g) of 7% at various rates of reinvestment over time.

As you can see, anything less than full reinvestment results in a lower CAR, and price appreciation rather than dividends accounts for a larger and larger percentage of the results. If the investor chooses to reinvest nothing and instead chooses to consume the dividend, the only source of growth is price appreciation.

To further illustrate the importance of price appreciation in returns, let's assume an annual price appreciation rate (g) of 0% at various rates of reinvestment.

Over 30 years assuming 100% reinvestment, a $1,000 investment in a stock with an initial dividend yield of 4% and price appreciation of 7% will be worth $24,690; if price appreciation is 0% it will be worth $3,243. When there's no price growth, you're just purchasing additional shares.

In other words, while we can clearly see the importance of reinvesting dividends in enhancing the benefits of compounding growth, we can also see that price appreciation matters more than the oft-cited studies suggest.

This isn't a dividend downer

By no means should this be taken as a knock on the power of dividends. Rather, it shows that investors also need to pay attention to price appreciation and valuation. Dividends alone don't drive returns.

While the academic studies over-emphasize and perhaps misrepresent the contribution of dividends to long-term shareholder returns, the studies remain an important part of the discourse about dividends and illustrate quite clearly how dividends enhance the benefits of compounding growth. Their lessons should still be heeded.

The more fully you can reinvest each dividend received, the higher your potential longer-term returns. A few ways that you can maximize your reinvestment rate are to hold your dividend paying stocks in tax-advantaged accounts like IRAs (US) and ISAs (UK), to compare your broker's reinvestment fees (if any) and policies (do they allow fractional reinvestment?) versus others, and to evaluate your reinvestment strategy.

Thanks for reading! Please post any questions or comments below.

Best,

Todd

@toddwenning on Twitter

Note: In the original post, I mislabeled CAR in the second formula and in the examples. It has now been updated. Apologies for the confusion.

Saturday, October 13, 2012

Should We Do Away With Dividend Yield?

We may not like it, but buybacks are here to stay. Management teams prefer buybacks for a number of reasons, even though those reasons may not always be in the best interests of their shareholders.

So ingrained are buybacks in today's market that some have called for an end to the classic definition of dividend yield (dividends per share / share price) to be replaced with a "modified" or "total" yield that includes buybacks ( (dividends + buybacks per share) / share price).

Indeed, Standard & Poors now includes a "dividend & buyback yield" column in its quarterly update on S&P 500 distributions. Ready or not, it's becoming a more commonly-used metric.

The game has changed...

The total yield approach is somewhat instructive as it helps explain a number of things that we've seen in the 30 years since Congress (via rule 10b-18) allowed companies to make greater use of buybacks.

The major thing total yield helps explain is why dividend yields over the past 30 years remain well-off historical averages. The chart below shows the dividend yield of the S&P 500 between 1960 and 2011 and compares it with the total yield of all U.S. companies since 1985 when buybacks started becoming a meaningful way of returning shareholder cash.

Recognizing there's only a slight difference between the 1960-2011 and 1985-2011 data, the major difference between the red and blue lines is buyback yield. Put in this perspective, the decline in dividend yield can be rationalized as a paradigm shift toward alternative ways of returning shareholder cash.

In fact, it shows that companies have become even more generous with distributions than in the past.

(Don't break out the party hats just yet...)

The next chart provides more granularity for the total yield period and shows the rise of buybacks as the primary means of returning shareholder cash between 1985 and 2011.

As you can see from these two charts, buybacks have only recently become a truly driving force in the total yield equation. Until 2004, dividends had accounted for the majority of distributions -- even during the dotcom boom.

Predictably, the buyback trend since 2004 has largely followed the market. When the market has been good and companies feel flush, buybacks have increased, and vice versa. Curiously -- and sadly -- as Michael Mauboussin points out here, M&A activity has generally followed this path, as well:

Its current market cap is $28 billion.

Long-term HPQ shareholders certainly don't feel any richer despite the $36 billion buybacks that should have been used to enhance shareholder value -- or in part distributed to shareholders as special cash dividends. Worse, most of the buybacks were fueled by borrowings and HPQ's debt/equity ratio increased from 13% in 2007 to 76% in the most recent quarter.

...but common sense remains common sense

There are companies that make prudent use of buybacks and no, I'm not completely opposed to them; however, general market data shows that, on average, buybacks are value destructive.

For this reason alone, I cannot accept the idea that we should do away with dividend yield and replace it with a total yield metric that includes buybacks. The two types of returning shareholder cash are simply not apples-to-apples.

The total yield metric is certainly instructive, but given the differences between dividends and buybacks and the track record of companies destroying value using buybacks, it's critical to keep dividend yield and buyback yield separate.

Hope you're having a great weekend! Thanks for reading.

Best,

Todd

So ingrained are buybacks in today's market that some have called for an end to the classic definition of dividend yield (dividends per share / share price) to be replaced with a "modified" or "total" yield that includes buybacks ( (dividends + buybacks per share) / share price).

Indeed, Standard & Poors now includes a "dividend & buyback yield" column in its quarterly update on S&P 500 distributions. Ready or not, it's becoming a more commonly-used metric.

The game has changed...

The total yield approach is somewhat instructive as it helps explain a number of things that we've seen in the 30 years since Congress (via rule 10b-18) allowed companies to make greater use of buybacks.

The major thing total yield helps explain is why dividend yields over the past 30 years remain well-off historical averages. The chart below shows the dividend yield of the S&P 500 between 1960 and 2011 and compares it with the total yield of all U.S. companies since 1985 when buybacks started becoming a meaningful way of returning shareholder cash.

|

| Source: S&P (via Aswath Damodaran) and Birinyi Associates and FRB Z.1. (via Michael Mauboussin) |

Recognizing there's only a slight difference between the 1960-2011 and 1985-2011 data, the major difference between the red and blue lines is buyback yield. Put in this perspective, the decline in dividend yield can be rationalized as a paradigm shift toward alternative ways of returning shareholder cash.

In fact, it shows that companies have become even more generous with distributions than in the past.

(Don't break out the party hats just yet...)

The next chart provides more granularity for the total yield period and shows the rise of buybacks as the primary means of returning shareholder cash between 1985 and 2011.

|

| Source: Birinyi Associates and FRB Z.1. |

Predictably, the buyback trend since 2004 has largely followed the market. When the market has been good and companies feel flush, buybacks have increased, and vice versa. Curiously -- and sadly -- as Michael Mauboussin points out here, M&A activity has generally followed this path, as well:

One shining example of this principle in action has been Hewlett-Packard, which repurchased $36 billion of its stock between 2008 and 2011.

Indeed, M&A and buybacks follow the economic cycle: Activity increases when the stock market is up and decreases when the market is down. This is the exact opposite pattern you’d expect if management’s primary goal is to build value. (His emphasis)

Its current market cap is $28 billion.

Long-term HPQ shareholders certainly don't feel any richer despite the $36 billion buybacks that should have been used to enhance shareholder value -- or in part distributed to shareholders as special cash dividends. Worse, most of the buybacks were fueled by borrowings and HPQ's debt/equity ratio increased from 13% in 2007 to 76% in the most recent quarter.

...but common sense remains common sense

There are companies that make prudent use of buybacks and no, I'm not completely opposed to them; however, general market data shows that, on average, buybacks are value destructive.

For this reason alone, I cannot accept the idea that we should do away with dividend yield and replace it with a total yield metric that includes buybacks. The two types of returning shareholder cash are simply not apples-to-apples.

The total yield metric is certainly instructive, but given the differences between dividends and buybacks and the track record of companies destroying value using buybacks, it's critical to keep dividend yield and buyback yield separate.

Hope you're having a great weekend! Thanks for reading.

Best,

Todd

Labels:

buyback,

capital gains,

Dividend,

total yield,

yield

Saturday, October 6, 2012

Where to Find Value in the Dividend Market Today

There's no question that dividend-paying stocks have become more popular in recent years as interest rates on fixed income and savings products declined.

Indeed, dividend-focused ETFs and mutual funds have experienced strong inflows, some higher-yielding stocks in rather staid industries (tobacco, utilities, etc.) are trading with multiples above their five-year averages, and gross S&P 500 dividend distributions will almost certainly hit a record high in 2012.

Contrarian investors will naturally raise an eyebrow or two at these developments.

Time to bail?

The heightened interest in dividends has led to some speculation that a "dividend bubble" might be afoot. As you might expect, massive debate has ensued among pundits, normally with the author taking a firm and uncompromising stance on one side or the other.

The problem isn't that either side hasn't made fair observations, but that the debate is all too frequently framed around whether or not there is in fact a "bubble" -- definitely the most overused term in financial media -- and misses the fruitful middle ground, leaving the reader without any actionable guidance ("Great, there is/isn't a dividend 'bubble'. What now?")

Instead, I find it far more instructive to critically examine the landscape as it stands today without being handcuffed to the bubble framework.

Is there "irrational exuberance" for dividend-paying stocks today? Relative to the exuberance we saw with dotcom stocks or housing, absolutely not. If there were, I don't think you'd see this trend in U.S. payout ratios.

It stands to reason that if investors really were falling over themselves to buy dividend stocks, companies would respond by paying out a greater percentage of earnings as dividends, so as to attract more investor interest. While some companies may have accelerated their dividend payouts for this reason, on average, that's not happening.

Instead, S&P 500 companies used buybacks over dividends to return cash to shareholders by nearly a 2:1 ratio in the second quarter. The trailing 12-month S&P 500 dividend payout ratio stands at just 32%.

Might some institutional investors be using buybacks to 'create' their own dividends? Maybe, but you could have just as easily have made the case for that in 2007 when dividends certainly weren't in style.

And yes, aggregate dividends of $67.31 billion in Q2 2012 set a record -- finally eclipsing the previous record of $67.09 billion set in Q2 2007. Flat nominal dividend growth over the course of five years is hardly an indication that corporations are opening the spigots to satiate investor appetite for dividends.

Are some dividend-paying stocks overvalued today? Yes. Judging by the multiples on some low-growth, high-yielding stocks today, I think it's likely that income-thirsty investors have in some cases reached for yield and bid the share prices above their fair value.

Similarly, so-called "quality" dividend-paying stocks -- that is, stocks with long track records of raising payouts each year (Aristocrats, Achievers, etc.) and investment-grade balance sheets -- as a group seem to be fully valued.

Are all dividend-paying stocks overvalued today? No. I think there's likely more value to be found in the lower-yielding areas of the market, as investors who are solely interested in current income are focused on the higher-yielding stocks and may not have the time horizon or interest to wait for the dividend to grow over time.

Where might there be value left among dividend-paying stocks? Investors who have just started building a dividend-focused portfolio are not likely to find many deep value opportunities in the high-yield or traditional "quality" space right now.

The most fertile ground for moderate- to high-yielding stocks today is likely found in stocks that have just recently started paying dividends (as they're not yet included in Aristocrat/Achievers screens and trackers), stocks that may have cut their payouts during the financial crisis but are on the path to recovery, and in smaller-cap stocks where the large funds are less likely to hunt for yield.

Bottom line

While there isn't a dividend "bubble", I will say that most of the low-hanging fruit has been picked. As such, you'll need to do a little extra homework if you hope to land some undervalued dividend-paying stocks with relatively good yields right now. It's no longer as simple as picking 12-20 stocks that everyone knows with investment-grade balance sheets and decades-long dividend track records. Yet there are still opportunities out there for investors willing to do the extra work.

(If you need a little help analyzing the stocks you come across, my free Dividend Compass tool can help you with your research.)

As always, stay disciplined and patient out there.

Best,

Todd Wenning

@toddwenning on Twitter

Indeed, dividend-focused ETFs and mutual funds have experienced strong inflows, some higher-yielding stocks in rather staid industries (tobacco, utilities, etc.) are trading with multiples above their five-year averages, and gross S&P 500 dividend distributions will almost certainly hit a record high in 2012.

Contrarian investors will naturally raise an eyebrow or two at these developments.

Time to bail?

The heightened interest in dividends has led to some speculation that a "dividend bubble" might be afoot. As you might expect, massive debate has ensued among pundits, normally with the author taking a firm and uncompromising stance on one side or the other.

The problem isn't that either side hasn't made fair observations, but that the debate is all too frequently framed around whether or not there is in fact a "bubble" -- definitely the most overused term in financial media -- and misses the fruitful middle ground, leaving the reader without any actionable guidance ("Great, there is/isn't a dividend 'bubble'. What now?")

Instead, I find it far more instructive to critically examine the landscape as it stands today without being handcuffed to the bubble framework.

Is there "irrational exuberance" for dividend-paying stocks today? Relative to the exuberance we saw with dotcom stocks or housing, absolutely not. If there were, I don't think you'd see this trend in U.S. payout ratios.

|

| Aswath Damodaran, Standard & Poors |

Instead, S&P 500 companies used buybacks over dividends to return cash to shareholders by nearly a 2:1 ratio in the second quarter. The trailing 12-month S&P 500 dividend payout ratio stands at just 32%.

|

| Source: Standard & Poors |

Might some institutional investors be using buybacks to 'create' their own dividends? Maybe, but you could have just as easily have made the case for that in 2007 when dividends certainly weren't in style.

And yes, aggregate dividends of $67.31 billion in Q2 2012 set a record -- finally eclipsing the previous record of $67.09 billion set in Q2 2007. Flat nominal dividend growth over the course of five years is hardly an indication that corporations are opening the spigots to satiate investor appetite for dividends.

Are some dividend-paying stocks overvalued today? Yes. Judging by the multiples on some low-growth, high-yielding stocks today, I think it's likely that income-thirsty investors have in some cases reached for yield and bid the share prices above their fair value.

Similarly, so-called "quality" dividend-paying stocks -- that is, stocks with long track records of raising payouts each year (Aristocrats, Achievers, etc.) and investment-grade balance sheets -- as a group seem to be fully valued.

Are all dividend-paying stocks overvalued today? No. I think there's likely more value to be found in the lower-yielding areas of the market, as investors who are solely interested in current income are focused on the higher-yielding stocks and may not have the time horizon or interest to wait for the dividend to grow over time.

Where might there be value left among dividend-paying stocks? Investors who have just started building a dividend-focused portfolio are not likely to find many deep value opportunities in the high-yield or traditional "quality" space right now.

The most fertile ground for moderate- to high-yielding stocks today is likely found in stocks that have just recently started paying dividends (as they're not yet included in Aristocrat/Achievers screens and trackers), stocks that may have cut their payouts during the financial crisis but are on the path to recovery, and in smaller-cap stocks where the large funds are less likely to hunt for yield.

Bottom line

While there isn't a dividend "bubble", I will say that most of the low-hanging fruit has been picked. As such, you'll need to do a little extra homework if you hope to land some undervalued dividend-paying stocks with relatively good yields right now. It's no longer as simple as picking 12-20 stocks that everyone knows with investment-grade balance sheets and decades-long dividend track records. Yet there are still opportunities out there for investors willing to do the extra work.

(If you need a little help analyzing the stocks you come across, my free Dividend Compass tool can help you with your research.)

As always, stay disciplined and patient out there.

Best,

Todd Wenning

@toddwenning on Twitter

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)