Long-term investing has gotten so popular it's easier to admit you're a crack addict than to admit you're a short-term investor. - Peter Lynch in 2000Having publicly written about investing since 2006, it's been interesting to observe changing investor opinion on long-term investing.

In the years following the financial crisis, for example, I would routinely receive reader comments and emails saying that long-term investing was flawed. And to be fair, they had numbers on their side, as ten-year trailing returns for the S&P 500 were unimpressive. As late as 2010, investors in the S&P 500 were looking back at a "lost decade" with negative ten-year total returns.

In the years following the financial crisis, for example, I would routinely receive reader comments and emails saying that long-term investing was flawed. And to be fair, they had numbers on their side, as ten-year trailing returns for the S&P 500 were unimpressive. As late as 2010, investors in the S&P 500 were looking back at a "lost decade" with negative ten-year total returns.It was easy to see why investor patience was in short supply. Even though the starting point of that ten-year period was the beginning of the end for the tech bubble, ten years is still a long time to wait for positive returns.

What a difference a few years of steady market gains makes. Since starting this blog three years ago and writing about the benefits of long-term investing, I have yet to receive any pushback on whether or not long-term investing works.

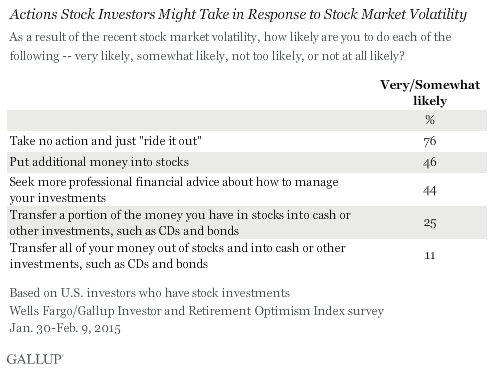

Indeed, a recent Gallup poll (h/t Ben Carlson at A Wealth of Common Sense) shows that the majority of investors today say they'll do nothing in the face of market volatility and nearly half said they'd put more money into stocks in the event of a sell off.

Of course, what investors say they'll do and what they'll actually do are two different things. (Everyone is a long-term investor when the market's going up, but we find out who really means it when the market falls.) However, the level of fear in the market seems to be rather low at the moment and that's not a great thing if you're looking to invest more into the market.

Does this mean you should do a 180 and become a daytrader? Absolutely not, but it does mean you should tighten rather than loosen your criteria for making a new investment. As one of Buffett's more famous sayings goes, "The less prudence with which other conduct their affairs, the greater prudence with which we should conduct our own affairs."

Related posts:

- 9 Tips for Becoming a More Patient Investor

- When Should You Sell a Good Stock?

- What's Your Investing Edge?

Best,

Todd

Subscribe to Clear Eyes Investing by Email